PAZYRYK, Siberia; Feb. 28, 2010 -- Every carpet tells a story. But few tell one as fascinating as the oldest intact carpet ever found.

PAZYRYK, Siberia; Feb. 28, 2010 -- Every carpet tells a story. But few tell one as fascinating as the oldest intact carpet ever found.It is the Pazyryk carpet, discovered frozen in a tomb beneath the Siberian steppe.

The carpet was woven sometime in the 5th century BC and recovered almost 2,500 years later when, in 1949, Russian scientists opened one of many burial mounds in the Pazyryk valley, in the Altai mountains south of Novosibirsk.

Because the tombs, where Russia borders with China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, were dug deep into the permafrost and covered with piles of timber and stone, the carpet and the mummified bodies of the nobles it accompanied emerged in a remarkably well preserved state.

Here is a picture of one corner of the carpet, which is now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The picture at the top of the page is a detail of one of the carpet’s horsemen.

Here is a picture of one corner of the carpet, which is now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The picture at the top of the page is a detail of one of the carpet’s horsemen.The century during which the carpet was put in the tomb is best known in the West for what was happening in ancient Greece at the time.

The 5th century was the time of the Greek-Persian wars, of Herodotus completing his “History,” of the construction of the Parthenon, of Sophocles writing ‘”Antigone,” and, finally, of the ruinous Peleponnesian war between Athens and Sparta.

But the story the carpet tells is a very different one from that of the ancient Greeks.

It tells the story of the Scythians, a partly settled, partly nomadic people whose home was the vast expanse of Eurasia north of Greece, Mesopotamia, Persia and China.

This is a picture of a Scythian horseman, made with an appliqué felt technique. It is from a wall hanging found along with the carpet in the Pazyryk tombs.

This is a picture of a Scythian horseman, made with an appliqué felt technique. It is from a wall hanging found along with the carpet in the Pazyryk tombs. The domain of the Scythians, who were Persian speakers and a fiercely independent part of the Greater Persian world, extended from modern Bulgaria, through Ukraine and Central Asia, to close to today’s Chinese border.

The basis of their power, and their trading wealth, was the huge herds of horses they raised. They are among the first peoples to be mentioned as mounted warriors and their mobility made them almost impossible to conquer.

At the same time, they were a conduit for trade along the Silk Roads, which carried goods between Persia, India, and China.

But if the horse-herding Scythians were mobile, they also were able to maintain the kind of rich court culture one usually associates only with city dwellers.

But if the horse-herding Scythians were mobile, they also were able to maintain the kind of rich court culture one usually associates only with city dwellers. They were able to due so thanks to their use of carriages like this one, which was found disassembled in the Pazyryk tombs.

Their carriages enabled them not just to easily move their tents and other necessities, but also carry along stores of luxury goods, some which they imported and others they produced themselves.

One of the things the Scythians are best remembered for today is their intricate gold jewelry, which regularly tours the world in museum exhibits.

The other thing they are best remembered for is the size of their royal burial mounds, known as kurgans, which sometimes could reach over 20 meters high. Inside, as in the Egyptian pyramids, nobles were buried with their treasure for use in the afterlife.

This map roughly shows the extent of the Scythian lands at the time of the Roman Empire.

This map roughly shows the extent of the Scythian lands at the time of the Roman Empire.The other great nomadic people of northern Eurasia at this time, located farther east, were the Turkic-speaking tribes.

Later the Turkic-speaking nomads would sweep west in a centuries-long confrontation with the Persian speakers that would be chronicled in classical Persia’s epic poems.

Still, if much is known today about the Scythians due to their mention in ancient histories and the excavation of their burial mounds, very little is known about their carpets and carpet culture.

The only certainty is that their carpets included both pile rugs (the only example of which is the Pazyryk) and felt rugs.

Here is a close-up of a felt saddle blanket found in the Pazyryk tombs.

Here is a close-up of a felt saddle blanket found in the Pazyryk tombs.Both the pile and felt work show a level of technical sophistication that makes it clear they belong to a very old artistic tradition.

But whether that tradition was the Scythians’ own or was borrowed from neighbors is impossible to know for sure.

Most carpet scholars believe the Pazyryk pile carpet could not have been woven in a nomadic setting in such a remote corner of the Siberian steppe.

Murray Eiland Jr. and Murray Eiland III note in their book 'Oriental Carpets' (1998) that the carpet "raises the question as to how pastoral nomads could have acquired such a technically proficient work of art."

They answer that "it could have been through trade, as some Chinese silk fabrics were found at Pazyryk and other early nomadic burials on the steppes."

Theories of the carpet's origin generally assume it was woven in either a major population center of Achaemenid Persia or perhaps an outpost of the Persian Empire nearer to Pazyryk itself.

If the carpet were made in Persia, that would make it not only the earliest intact carpet ever found but also a striking example of the early carpet trade.

With its motifs of horsemen and deer, it may have been expressly designed for export to the steppes. Or, it might have been specifically commissioned by a Scythian chief.

Here is a saddle found in the Pazyryk tombs, showing the same kinds of tassels that can be seen on the saddles depicted in the carpet.

Here is a saddle found in the Pazyryk tombs, showing the same kinds of tassels that can be seen on the saddles depicted in the carpet.The mystery of the Pazyryk carpet's exact origin may never be solved. And perhaps it does not need to be, because the Pazyryk itself makes a still more important point.

That is, that carpets, whether woven at home or imported from afar, seem to be a universal human interest as old as time.

How did the Scythians use their rugs which – judging by their inclusion in a royal burial tomb – were clearly prized possessions?

The answer must be left to the imagination.

One possibility is that the carpets were at the center stage of decorating schemes that also included elaborate furniture like this table, also found in the Pazyryk tombs.

One possibility is that the carpets were at the center stage of decorating schemes that also included elaborate furniture like this table, also found in the Pazyryk tombs.Perhaps the lion motifs of the table combined with the motifs of both natural and fantastic creatures on the carpets to fill Scythian tents with the echoes of the things their culture most prized.

The Pazyryk carpet alone includes horses, griffins, and deer. Its size is 180 x 198 cm (5'11" x 6' 6").

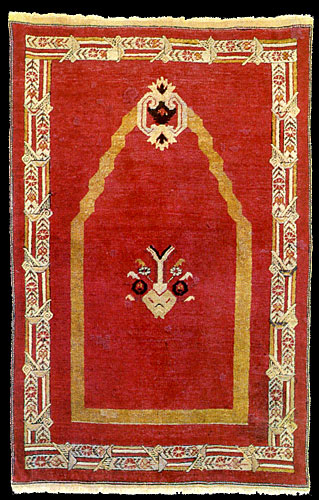

Today, the Pazyryk carpet is regularly reproduced by modern carpet weavers who find its design still has a magical appeal.

This high-quality replica is produced by weavers working in northern Afghanistan using natural dyes and handspun wool. It is available from Nomad Rugs in San Francisco.

This high-quality replica is produced by weavers working in northern Afghanistan using natural dyes and handspun wool. It is available from Nomad Rugs in San Francisco.It is interesting to think of the Pazyryk carpet, placed in a royal tent, as the world’s earliest known example of a room with a rug.

And it is even more fascinating to think that this earliest known example is so stunning in its beauty that it can equally express all the pleasure and excitement people have taken in furnishing their rooms with rugs ever since.

#

RETURN TO HOME PAGE

#