HANOVER, February 6, 2009 -- Many rug dealers say they can tell what kind of rug you will buy as soon as they meet you. If they know your nationality, they feel even more confident.

HANOVER, February 6, 2009 -- Many rug dealers say they can tell what kind of rug you will buy as soon as they meet you. If they know your nationality, they feel even more confident.One such dealer is Khairi Ezzabi, a Libyan who travels the world looking for luxury goods to import back home to Tripoli. He buys and sells in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Along the way, he has learned a great deal about all three markets.

We recently met Mr. Ezzabi in a zimmer frei in Hanover, Germany. The occasion was Domotex, the carpet world's biggest trade show that takes place every January. The show attracts thousands of people, more even than the huge number of hotels in this trade-fair city can accommodate. So, many visitors find themselves taking rooms in private homes, something that leads to impromptu acquaintances.

As the guests come down for breakfast, the lady of the house introduces them to one another. The table is set with all the riches of German hospitality and instantly puts everyone in a good mood. There is bread, rolls, butter, jam, and honey, plates of ham, salami, and different cheeses, soft-boiled eggs, oranges, apples, and slices of kiwi, and then, as if waiting for dessert, an assortment of sweet buns and pound cake.

The conversation flows easily.

"Please tell our guest that the salami is made of lamb, and the ham is made of chicken," Frau Ripphoff says in German. But before anyone can play the part of translator, the well-traveled Mr. Ezzabi waves away the need for words with his hand.

"I was here before, two years ago," he replies in English. "I remember her kindness from before."

Everyone is pleased. The small breakfast corner suddenly doubles in size with the expansive good manners of the East. As the windows slowly turn from night-black to grey with the late winter sunrise, Mr. Ezzabi fills a plate with pieces of bread, abstains from everything else, and takes time to talk.

He is a wonderful talker, punctuating with delighted giggles what he knows will be outrageous observations. But he also knows much of what he says will be true. After all, hasn't he seen it with his own eyes?

"What do people want from oriental rugs?" he asks, repeating a visitor's question. "They want different things."

The French, Italian, and Spanish want imperfection, he says. They want to be able to see where the weaver ran out of a particular color here or made a wrong knot there.

The French, Italian, and Spanish want imperfection, he says. They want to be able to see where the weaver ran out of a particular color here or made a wrong knot there."The Parisians pride themselves on being able to recite the whole personal story of the carpets in their home." He giggles.

Visions of tiny, high-priced boutiques that offer just a few nomadic and tribal pieces float before the eyes. The Paris dealers are not selling rugs, they are selling flights of fancy -- like travel agents. Or it that too much of an exaggeration?

But Mr. Ezzabi is too charming to quibble with.

"The Germans," he continues, eyeing the perfect breakfast table before him but taking only some more bread, "want technical perfection."

"The Germans," he continues, eyeing the perfect breakfast table before him but taking only some more bread, "want technical perfection." In Berlin they like a proper relationship between price and workmanship. And they don't like stories that sometimes sound like excuses for a weaver's mistakes.

The Libyan dealer has been all around the world and clearly knows something of human nature. He lovingly pours a cup of strong black tea. He does not want to offend, he likes everywhere he visits. Should he continue?

Arab, Russian, and Bulgarian buyers share a third taste in carpets, he says. They will spend far more for a single carpet than anyone else. And it will be for a big carpet, to fill a big room.

"Prestige," he says. "They like black and gold colors."

It is impossible to know if Mr. Ezzabi has become rich with these formulas. He is dressed in a simple gray suit of light material that looks Italian but has an accent of hand-tailoring in a distant land. He is trim, with impeccably courteous manners, and middle-aged in way that is impossible to pin down.

What are things like in Libya, one asks. After all, one doesn't meet a Libyan businessman every day.

"I only know Tripoli and the capitals of the world," he replies. I am always traveling."

And the desert, with its starry night sky that shines so bright above the vast dark sands?

"The oil men say it is beautiful."

One can only wonder what kind of carpets he has come to Hanover to find. At the fair, there are carpets from everywhere: Iran, Turkey, China, India, Pakistan. What will he choose?

"I don't know yet," he says. "The last time I came I bought just one carpet."

The carpet was from Mirzazadeh, one of the most famous Persian producers from Tabriz. But it was not a classical carpet, it was a pictorial carpet with a scene from Omar Khayyam.

The cost was over 100,000 euros and the workmanship extraordinary, with some 2,000 knots per square inch (31,000 knots per square decimeter). He took it to Tripoli and put it in the window of his shop in the heart of downtown. Cars crashed into each other on the road when they passed by.

The cost was over 100,000 euros and the workmanship extraordinary, with some 2,000 knots per square inch (31,000 knots per square decimeter). He took it to Tripoli and put it in the window of his shop in the heart of downtown. Cars crashed into each other on the road when they passed by."People suddenly stopped their cars to stare at the carpet," he says. "They admired it because it is as perfect as a picture, as perfect as a color photograph. No one could believe it is just a carpet."

And did he sell it?

"No," he says. "It is excellent advertising for my shop. So, I keep it in the window. And I like it too much myself to sell."

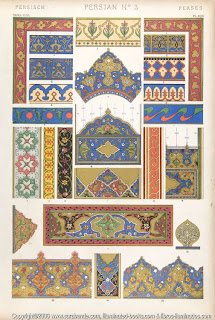

(The photo at the top of this article is of a Mirzazadeh pictorial carpet.)

#

RETURN TO HOME PAGE

#

Related Links:

Mirzazadeh Carpets