INDIANAPOLIS, USA; March 6, 2009 -- The "It" girls of the 1920s -- the Flappers -- did a lot to usher in the modern age.

INDIANAPOLIS, USA; March 6, 2009 -- The "It" girls of the 1920s -- the Flappers -- did a lot to usher in the modern age. They were the first to stop wearing the waist-constricting corsets that gave so many women before them the look of walking -- and fainting -- hourglasses.

They danced wild dances -- the Charleston and the Bunny Hug -- to ragtime and jazz taken from the previously ignored culture of Black America.

And they cut their hair short and smoked and drank like men, presaging the days when women would join the workforce and become financially as well as socially independent.

All this revolutionary behavior might seem whimsical until you think of what directly preceded it: World War I. The previous world order had ended in what -- politics aside -- was collective suicide. Many people believed it was absolutely necessary to try something new.

But what does this have to do with carpets?

One of the less well-known ways the Flappers anticipated modern times was also by being interested in "ethno" styles.

Their early ethno-look did not just include feathered headbands to liven up a party outfit -- already a step too far for many people today. It also featured beaded purses in a variety of designs inspired by oriental carpets and textiles.

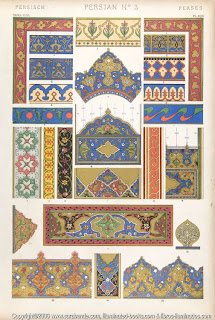

Their early ethno-look did not just include feathered headbands to liven up a party outfit -- already a step too far for many people today. It also featured beaded purses in a variety of designs inspired by oriental carpets and textiles.The beaded carpet purses came in a huge variety of patterns. They ranged from Turkish prayer carpets, to Caucasian rugs, to Persian medallion carpets, to Turkmen tribal designs, to Indian textile motifs. But unlike most ethno products today, they were not made in the East as one might expect, but in the United States and Europe, particularly in France.

The story of these beaded oriental carpets was told recently by an exhibit of 70 such purses at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) in Indiana. The exhibit, entitled Shared Beauty: Eastern Rugs & Western Beaded Purses began May 31, 2008 and ends April 5 this year.

Niloo Paydar, curator of textiles and fashion arts at the IMA, says oriental carpet designs were not something originally associated with beaded purses, which have a long history of their own from the late 19th century through the early 20th.

Much more typical designs for beaded purses were chinoiserie, landscapes, flowers and occasionally people, and mostly these designs were taken from paintings and other arts of the period. Here is one such landscape purse (right).

Much more typical designs for beaded purses were chinoiserie, landscapes, flowers and occasionally people, and mostly these designs were taken from paintings and other arts of the period. Here is one such landscape purse (right).In the 1920s, the demand for beaded purses reached its height. One reason may be that they were a perfect accessory for beaded evening dresses, which were an integral part of flapper-era costumes. This apparently created a desire for still more designs, and oriental carpet patterns suddenly joined the menu.

Paydar says the use of carpet designs was surprising because their patterns did not go particularly well with the patterns of the Jazz Age dresses, which were mainly art deco.

Still, their popularity may reflect the fact that during this same period Orientalism was still in vogue and eastern carpets were commonplace in western homes. The best-traveled could take package tours on the Nile or steamers to Istanbul or go on around the world from one European colonial possession to the next. Eastern motifs and the exotic associations that went with them were part of the times.

But precisely when the oriental beaded purses first appeared is hard to know.

Paydar says most beaded purses, which can be of glass or metal, offer very few clues to the date they were made. There are some trends, such as drawstrings being used earlier, and clasps later, for closing the purses, and some lining materials were used before others. But putting together a precise history of the purses is difficult indeed.

Paydar says most beaded purses, which can be of glass or metal, offer very few clues to the date they were made. There are some trends, such as drawstrings being used earlier, and clasps later, for closing the purses, and some lining materials were used before others. But putting together a precise history of the purses is difficult indeed. The 70 purses exhibited by the IMA come from a single private collection in California compiled by Stella and Frederick Krieger. The Museum juxtaposed the purses with rugs from its own holdings plus some more loaned by local rug collectors.

"I personally have an interest in exhibiting eastern and western designs alongside each other and talking about how they influence each other and how influence is not always west to east," Paydar says. "Who would have thought carpet patterns would have become a fashion accessory?"

She also says that the museum has found that exhibiting beaded purses, which are familiar to many Americans, is a good way to teach visitors about something that today is less familiar: oriental carpet designs.

She also says that the museum has found that exhibiting beaded purses, which are familiar to many Americans, is a good way to teach visitors about something that today is less familiar: oriental carpet designs.That may seem ironic, given how popular both once were together. But over the decades things have changed. Oriental carpets are no longer a staple of American household furnishings but beaded purses -- in a whole variety of designs -- remain a very popular arts and craft item.

In the United States there is a huge community of bead purse collectors and almost every city has a bead society, Paydar says. Many enthusiasts make their own bead purses, so the tradition is very much alive today.

(Photos from top to bottom: Carpet Purse from Collection of Fred and Stella Krieger; actress Norma Talmadge; landscape purse courtesy Purse Treasures; carpet purse from Collection of Fred and Stella Krieger; Shared Beauty exhibit IMA.)

#

RETURN TO HOME PAGE

#

Related Links

Indianapolis Museum of Art: Shared Beauty -- Eastern Rugs & Western Beaded Purses

Purse Treasures: Geometric and Carpet Beaded Purses

The Jazz Age: Flappers, Music and Dancing