PARIS, October 22, 2011 – It is a strange thing that during Europe's long love affair with oriental carpets, the love once cooled for almost a hundred years.

PARIS, October 22, 2011 – It is a strange thing that during Europe's long love affair with oriental carpets, the love once cooled for almost a hundred years. That period roughly corresponds to Europe's Baroque era when, instead of importing oriental carpets as they had for centuries, European nobility began buying European-made carpets instead.

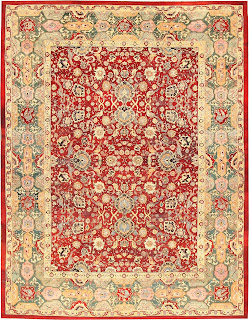

Those carpets, like the Savonnerie carpet shown here, looked nothing like the Turkish and Persian styles depicted in the Renaissance paintings of earlier generations. Rather, they were specifically woven in Europe beginning around 1644 to compliment the new baroque architecture of European palaces and mansions.

In fact, the new European carpets did not just compliment baroque architecture, they often directly imitated baroque ceiling designs. That enabled Europe's designers to do what they had never done so lavishly before: swaddle the wealthy in a single style of interior decoration from head to foot.

The single style – Baroque and its spin-off Rococo - conveyed power and opulence and corresponded with Europe's own rising sense of economic wealth and importance.

Still, if the development of French-made Savonnerie and Aubusson carpets, or similar Axminster and Wilton carpets in Britain, suggests that Europeans somehow entirely lost interest in Eastern designs at this time, the impression would be wrong.

Ironically, the Baroque Era in which Europeans lost interest in Oriental rugs coincides with what was Europe's greatest ever period of fascination with all things Turkish. That fascination was so widespread that it had a name: Turquerie.

Ironically, the Baroque Era in which Europeans lost interest in Oriental rugs coincides with what was Europe's greatest ever period of fascination with all things Turkish. That fascination was so widespread that it had a name: Turquerie.Here is a portrait of Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresa at the height of the Turquerie fad which swept Europe in the 1600s and 1700s. She is dressed in a Turkish costume and is holding a mask. It was painted circa 1744 by Martin van Meytens.

How the Turquerie fad took shape and why it did not include rugs is one of the stranger stories in carpet history. After all, Turquerie – the French-coined word for Europe's taste for Turkish styles – could be found in many other arts: from dress, to fabrics, to interiors, to porcelain.

To understand Turquerie – which was a precursor of, but quite different from, Orientalism – one has to return to Europe of the 1600s. It was a time when Europe's relations with the Ottoman Empire changed dramatically.

Prior to the the mid-1600s, the Ottoman Empire had been Europe's most feared neighbor. The Empire had grown with astonishing speed from its start two centuries earlier and directly annexed much of Eastern Europe, including Greece.

Prior to the the mid-1600s, the Ottoman Empire had been Europe's most feared neighbor. The Empire had grown with astonishing speed from its start two centuries earlier and directly annexed much of Eastern Europe, including Greece.But by the mid-1600s, the Ottoman's power to expand deeper into Europe was clearly spent. The Empire's second attempt to take Vienna with a 60 day siege in 1683 ended in a disastrous route and, though Eastern Europe would remain under the Ottomans almost another two centuries years, fear of the Empire in the rest of Europe subsided.

Instead, Western Europeans suddenly became very interested in the art and lifestyle of the foe they no longer feared. To dress up for palace balls "alla Turca" became the rage. And the practice of drinking coffee – something that had previously reached only Venice from Istanbul -- suddenly spread across Europe.

In Vienna, one of the first cafes was the House under The Blue Bottle, which opened in 1686. Its origins, just three years after the Ottoman siege of the city, perfectly illustrates the new fascination with the East.

In Vienna, one of the first cafes was the House under The Blue Bottle, which opened in 1686. Its origins, just three years after the Ottoman siege of the city, perfectly illustrates the new fascination with the East.The Blue Bottle's proprietor, Georg Franz Kolschitzky, had lived in Istanbul as a young man and learned Turkish. During the siege he used his language skills to spy on the Ottoman camp. Legend says that afterwards he claimed the coffee beans the Turks left behind as his share of the war booty and used them to start his business. For decades, he ran his café dressed as an Ottoman cafe owner, as this painting from the time shows.

Like any fad, Turquerie was a mix of reality and fantasy. It came when still very few Europeans traveled to the East and it was heavily influenced by Europeans' own imaginary visions of oriental luxury, Ottoman customs, and even harems.

But even if Turquerie was in large part make-believe, there is no doubt that genuine curiosity about -- and even admiration of the Ottoman Empire – was equally part of it.

When one of the most famous, and large-scale, weddings of the time took place in Dresden in 1719, the celebration included days of specially themed events.

On one of those days, the newlyweds (the Prince-elector of Saxony, Friedrich August II, and the Austrian Archduchess Maria Josepha) had a palace in ‘Turkish style’ erected complete with a corps of janissaries. The guests, who included an Ottoman ambassador, were requested to appear in Turkish costume.

Similarly, it became the rage for noble women to have their portraits painted wearing a Turkish costume and in an Oriental setting, sometimes even sitting on an oriental carpet.

Similarly, it became the rage for noble women to have their portraits painted wearing a Turkish costume and in an Oriental setting, sometimes even sitting on an oriental carpet. Here is one portrait from the time, Mademoiselle de Clermont "en Sultane" painted in 1733 by Jean-Marc Nattier.

A much more famous sitter, the Marquise de Pompadour, commissioned three portraits of herself dressed as a Sultana in 1750. The portraits not only allowed the sitters to appear in exotic fashions but also to abandon their body-constricting corsets -- something that would not become possible again in Western fashion until the 1900s.

Men also took part. In the 1700s, it was in fashion for wealthy men to smoke Turkish tobacco in a Turkish pipe, sometimes wearing a Turkish robe. And when people went out to the opera, it was possible to find Turquerie there, too.

The most famous of the Turquerie operas – still played today – is Mozart's 'The Abduction from the Seraglio'. It was first presented in 1782, but 13 other similarly themed operas predate it. Often the productions clothed the singers in authentic Ottoman fashions, knowing that theater goers were curious about them.

Even in architecture Turquerie found a place, this time in the form of Ottoman-inspired pleasure domes.

Even in architecture Turquerie found a place, this time in the form of Ottoman-inspired pleasure domes. Here is the central building of a "Türkischer Garten" built between the years of 1778-91 in southwestern Germany. It is part of the Schwetzingen Castle, the summer residence of the rulers of the then German state of Baden-Württemberg.

One could easily imagine that so much interest in the Ottoman Empire would have to increase interest in that most essential symbol of the orient of all – carpets. But the fact that Europe's taste in carpet patterns went in an entirely different direction may only prove that, ultimately, Turquerie was more a measure of Europe's growing sense of self assurance than of cosmopolitan tastes.

Throughout the 1600s, when Turquerie began, and through the 1700s as it continued, the "gout Turque" coincided with the greatest period of expansionism in European history. It was a fad in an epic period that included the transformation of the New World and the creation of sea trading networks and ultimately colonies across Asia.

That meant that the key status symbols European society would have to be European too. Whereas wealthy Europeans in the Renaissance showed off their Turkish carpets to underline their rich status, the people of the late 1600s and early 1700s centuries furnished their mansions with European-woven baroque carpets instead.

Here is an antique Axminster, woven in Britain, that reflects the English taste of the time. It is available from the Nazmiyal Collection in New York.

Here is an antique Axminster, woven in Britain, that reflects the English taste of the time. It is available from the Nazmiyal Collection in New York.Interestingly, Europe's overwhelming preference for baroque carpets over oriental ones would not last long. By the mid 1700s, the taste for oriental carpets would begin returning with redoubled strength as Europe's view of the East started to dramatically change again.

This new change, seen most visibly in Napoleon's military expedition to Egypt in 1798, would come as Europeans directly entered into the life of the Orient as never before. It, too, would be accompanied by a new fad: Orientalism. But that is the subject of another story (see: Orientalism and Oriental Carpets).

#

RETURN TO HOME

#