NEW YORK, June 15, 2011 -- If there is a pinnacle to the rug business, it is the antique carpet trade.

NEW YORK, June 15, 2011 -- If there is a pinnacle to the rug business, it is the antique carpet trade. It is not only where people are willing to spend the most on a carpet they admire but also where dealers take the greatest risks.

Why risks?

Because to be successful, a dealer not only has to invest huge amounts of money in inventory. He or she also has to hope the global economy stays strong enough to create enough buyers to keep turning the inventory over and make the business prosper.

That's why Tea & Carpets welcomed the opportunity recently to interview one of the most successful people in the antique carpet trade, Jason Nazmiyal.

His New-York based company Nazmiyal Collection has been a leading name in the antique carpet world for decades. If anyone can describe the ins-and-outs of the business he can.

We started with this question: How much has the economic downturn affected the antique carpet market?

The answer is: a lot. Since 2001, he says, the antique market has been under heavy pressure. That's because the purchase of antiques is related to the performance of the stock market. When people's investments do well, they spend their extra earnings on luxury items, when not, not.

The goods Nazmiyal specializes in – room-sized decorative antique rugs – are luxury items running from $ 20,000 to $ 200,000. So, he has felt the pressure firsthand.

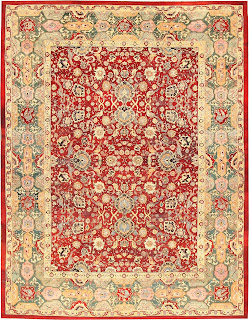

The goods Nazmiyal specializes in – room-sized decorative antique rugs – are luxury items running from $ 20,000 to $ 200,000. So, he has felt the pressure firsthand. Shown here is an antique Agra currently available from the Nazmiyal Collection.

Buying antique rugs, Nazmiyal explains "is more about what people feel than what they need." And over the past years, when even CEOs have worried about losing their jobs, what many people have felt is the urge to be cautious.

But how that caution gets expressed in the rug market can be surprising.

What many interior decorators advised their clients to do during the worst of the downturn was to buy new rugs instead of antique ones, because they are less expensive.

And, as that caused antique rug inventories to pile up, many antique rug dealers followed suite. Rather than invest their capital in more inventory, they invested in producing new rugs themselves, instead.

Nazmiyal did not follow that strategy, but he says for many dealers it made economic sense.

Here's why: To sell a $ 25,000 antique rug, you have to have half a dozen similarly expensive pieces for the client to choose from. But to sell a room-sized new carpet you need only show a $ 200 weaving sample.

If the sample satisfies the client, weaving can go ahead with just a fifty percent deposit, with the rest to be paid when the rug is delivered.

Here is another antique Agra carpet, with a flower design, available from Nazmiyal Collection.

Here is another antique Agra carpet, with a flower design, available from Nazmiyal Collection.The Nazmiyal Collection weathered the storm without switching to new rugs because its inventory is large and it has an extensive website with global clients. But, perhaps most valuably, the company's long-standing reputation for quality assures designers and others seek it out.

Today, with the economy showing signs of recovery, the antique carpet market is slowly stabilizing again.

Over the past six months, Nazmiyal says, the drift to new rugs has reversed and buyers are returning to vintage pieces.

The reasons they are returning are all the classic ones for which people value antiques. Compared to new rugs, antique rugs have greater interest of history and provenance, they have a patina that will take new carpets decades to acquire, and you don't have to wait six months for them to be woven.

There is another question that always fascinates people about the antique carpet business and that is the way it is influenced by changes of taste and style.

So, we asked how much tastes in antique rugs have changed over recent years and what is in demand now.

The answer, again, was surprising. Over the last 10 years in the United States , Nazmiyal says, decorators grew tired of busy Persian designs. They moved to East Turkestan rugs, for example, instead. Such rugs offered simpler designs and more monochromatic, muted colors.

Here is an antique Khotan available from Nazmiyal Collection.

Here is an antique Khotan available from Nazmiyal Collection.But over the past six months, things have shifted once again. Now high-end decorators are looking for traditional designs and bolder colors.

What drives the taste changes is a mystery. But the way it works is through the power of a handful of famous tastemakers.

Nazmiyal estimates that in New York City, there are about five "phenomenal designers" who are the trendsetters of our time and whom all the other designers watch. When their taste in fabrics, wallpapers, and other furnishings changes, so do the kinds of carpets the decorating world wants.

Interestingly, the designers themselves may or may not know much about the history of oriental carpets. "Some of the New York designers are so well trained to see beautiful things," he says, "that they don't need to know rug history and styles. They can just be confident of their own taste."

Does this mean that everywhere fashions change as if on cue? Not at all. There is still plenty of room for regional differences and there are variations in what kinds of antique rugs people want even from city to city.

Nazmiyal says that in Atlanta, for example, there is equal demand for beautiful carpets with medallion or all-over designs. But in New York, decorators only want all-over designs because they feel medallion designs fit less flexibly with current styles.

Similarly, there are trans-Atlantic differences.

In Europe, where houses and apartments tend to be smaller than in the United States, a 9 x 12 foot carpet is about the maximum any room can absorb. That makes a big rug, like a Sultanabad or Hajji Jalili, less desirable. And it gives people reasons to prefer smaller yet still highly visible rugs, like Caucasians, instead.

Here is an antique Sultanabad available from Nazmiyal Collection.

Here is an antique Sultanabad available from Nazmiyal Collection.One could pose questions about the antique rug trade all day and still never finish. So, we ask a final question about something most people only dream of. That is: what rug do you select for your own house when you have virtually every possibility available in your inventory?

Nazmiyal says he has a mix. He keeps a silk and wool Tehrani woven in 1920-21 with blues and whites in his library. And an early Agra in his living room.

Then he has to laugh. Like many carpet enthusiasts, he has a small obstacle to bringing home ever more antique pieces, as much as he might want to.

"My wife likes new things, not old ones," he says. "So when I bring an antique rug home, it has to be clean and with a full pile and look like a new rug."

How familiar does that sound? Sometimes the husband is the collector, sometimes the wife, and always compromises have to be found.

"But over time," he adds, "she's come to like antique rugs much more. It only took 15 years."

May all families enjoy such peace. And thanks again to Jason Nazmiyal for sharing his experiences with us.

#

RETURN TO HOME

#