ISTANBUL, January 29, 2010 -- Can a single carpet style symbolize the sudden decline of a country’s carpet making tradition?

ISTANBUL, January 29, 2010 -- Can a single carpet style symbolize the sudden decline of a country’s carpet making tradition?Many European carpet collectors once regarded this carpet – a so-called Mejid rug – just that way.

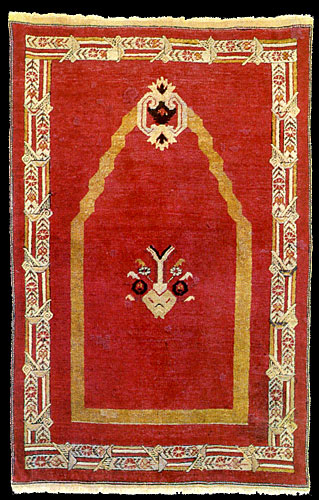

The rug is typical of a whole class of small-size, town-woven carpets that appeared in the mid-1800’s. It was a time when the Ottoman Empire was moving rapidly toward its final eclipse in 1923.

The rugs are striking for several reasons. One is their distinctly non-Anatolian look. The other is that, even though they were clearly influenced by the West’s own artistic values, Europeans at the time found them distasteful and fled from them.

How did these rugs come about and why were they popular in Turkey at the time?

The place to begin the story of the rugs is with their namesake, Sultan Abdul-Mejid.

He reigned from 1839 to 1861, during a time of massive threats to the empire’s traditional way of life. His efforts to fend off those threats by Westernizing many Ottoman institutions reached to every level of society, including the Arts. But the results were often mixed.

Abdul-Mejid came to the throne just as one of the empire’s prize possessions, Egypt, had permanently broken away. That followed the earlier loss of Greece and dramatically underlined the need to modernize both the army and to build loyalty among the empire's far-flung, multi-national subjects.

Abdul-Mejid came to the throne just as one of the empire’s prize possessions, Egypt, had permanently broken away. That followed the earlier loss of Greece and dramatically underlined the need to modernize both the army and to build loyalty among the empire's far-flung, multi-national subjects.Abdul-Mejid, like his father Mahmud II before him, looked to France and the ideals of the French Revolution for inspiration.

At the time, monarchies everywhere were awed by the way ordinary Frenchmen had enlisted en-masse in the Revolution’s armies to defend the values of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, and how Napoleon had later harnessed that power to all but conquer Europe. Many kings realized that their future depended upon at least partially making their societies more equitable.

Abdul-Mejid sought to transform Ottoman life by introducing the first of what would be many attempts at “Tanzimat,” or “Reordering” over the next decades.

The reforms attempted to stem the tide of nationalist movements within the Ottoman Empire by enhancing the civil liberties of non-Turks and non-Muslims and granting them equality throughout the Empire.

They also established a new system of state schools to produce a new generation of government officials more open to European technologies and administrative practices.

But the reforms were not only changes in substance but of style. Abdul-Mejid built Dolmabahce Palace in the French baroque manner, decorated it the same way, and moved there from Topkapi Palace. He also dressed in the European fashion and government functionaries began to do the same.

But the reforms were not only changes in substance but of style. Abdul-Mejid built Dolmabahce Palace in the French baroque manner, decorated it the same way, and moved there from Topkapi Palace. He also dressed in the European fashion and government functionaries began to do the same.Over time, the new European dress-code would fully replace the complicated Ottoman hierarchy of different clothing styles and even shoe colors which had distinguished officials by rank and office. It consisted of a monotonous, long-tailed frock coat that was called the “stambouline” in the West and, more facetiously, the “bonjour tuxedo” in Turkey. Like new uniforms for the army, the coat was intended to change the mindset of those who wore it.

The message was not lost upon Turkish artists, including weavers, who closely watched court styles.

Entrepreneurs responded with new European-flavored designs of their own. One answer was the “Mejid” carpet, which gained wide domestic popularity.

Entrepreneurs responded with new European-flavored designs of their own. One answer was the “Mejid” carpet, which gained wide domestic popularity.The “Mejids” clearly reflect the Francophile taste of the sultan, though it is not known whether the sultan liked them himself. They were woven in bright pastel shades and decorated with sparse, natural-looking flowers or even rococo swirls. It was a huge departure from Turkey’s own design tradition of non-naturalistic ornamentation and richly concentrated colors.

Here is a carpet woven in Ghiordes at the time. The carpet is available to collectors from the Nazmiyal Collection in New York.

How much any empire can stave off collapse by adopting new models at times of crisis is debatable. Abdul-Mejid’s efforts ran into huge obstacles, not the least of which were the Western European powers themselves.

They loaned him massive amounts of money to buy weapons to confront the expanding Russian empire, but attached fatal conditions to the loans.

The conditions were demands for trade concessions to open the empire’s raw materials -- wool, cotton, silk and coal -- to European businesses and its markets to European products, including textiles. The results of this, too, were soon visible in the carpet industry and its commercial hub, the Istanbul bazaar.

Until 1830, the Ottoman Empire was still largely a self-contained and self-sufficient space. But with the opening to the West, its manufacturers suddenly came into direct competition with the industrial revolution. European textiles flooded the market and domestic producers found it impossible to compete.

Until 1830, the Ottoman Empire was still largely a self-contained and self-sufficient space. But with the opening to the West, its manufacturers suddenly came into direct competition with the industrial revolution. European textiles flooded the market and domestic producers found it impossible to compete.Worse still for the domestic producers, the introduction of European fashions in the court harem caused a wave of emulation among Otttoman women. Dresses were made of European rather than local fabrics and the market for fine Ottoman silks collapsed.

Celik Gulersoy in his 1980 book ‘Story of the Grand Bazaar’ sums up the process this way:

“When ten thousand hand looms disappeared, villages could no longer be closed production units and the villagers turned into laborers and imported European goods rapidly took the place of domestic textiles in the Empire’s markets.”

The new shopping focus was the Bonmarches, the borrowed-from-French generic name for the shops erected in European style on the main avenue of Istanbul's chic Beyoglu district.

In 1881, a visiting English writer, Lady Brassey, described in her book ‘Sunshine and Storm in the East’ how rich Turkish ladies with their servants visiting the Grand Bazaar were surrounded by the treasures of the East but demanded the merchants show them Western goods instead, though these were mostly second quality. She regarded it as very strange.

By the turn-of-the-last century, the Grand Bazaar itself lost its most distinctive feature: the merchants sitting passively on wooden divans with their cupboards full of goods behind them. That, too, gave way to the new European style.

By the turn-of-the-last century, the Grand Bazaar itself lost its most distinctive feature: the merchants sitting passively on wooden divans with their cupboards full of goods behind them. That, too, gave way to the new European style.The arches lining the walls of the old Bazaar were connected to form shop facades and the merchants took to standing in their doorways.

In many cases, the merchants had no better choice because their new premises were no bigger than telephone booths. To complete the image of shops on a European street, they added signs and advertising above their doors.

During these decades, the Ottoman carpet production industry changed equally dramatically. Western capital entered the business and the Western market became the driving force of almost all the large-scale carpet manufactories.

Miroslav Jungr observes in his 2005 book ‘Oriental Carpets:’

Miroslav Jungr observes in his 2005 book ‘Oriental Carpets:’“The European powers brought every aspect of mass production to bear on the weaving process, including using synthetic dyes and demolishing traditional design schemes. Floral patterns, beloved by foreign customers, became standard even though – with a few exceptions such as medallion ushaks – they had never been part of the Turkish tradition.”

Curiously, the Mejids, the Turkish weavers’ own early experiment with incorporating European styles, were completely overlooked in Europe. Jungr notes their stylized flowers and mostly shiny colors did not correspond to the cosmopolitan taste of the time. But in Turkey they remained popular even after the death of Sultan Abdul-Mejid himself in 1861.

Only today, as their story is becoming better known, are the Mejids beginning to win respect from collectors. And that is partly because of the bittersweet story they tell of the end of one era and the start of another.

#

RETURN TO HOME

#