BISHKEK, April 25, 2008 – When one imagines the vast steppes of Central Asia, yurts and felt carpets come quickly to mind.

BISHKEK, April 25, 2008 – When one imagines the vast steppes of Central Asia, yurts and felt carpets come quickly to mind.It is from sheets of plain white felt that yurts are built, and it is with colorfully patterned felt that they are decorated inside. The result is a warm and cheerful shelter that served Central Asia’s nomads well for thousands of years.

If you drive along Kyrgyzstan's endless chains of Celestial Mountains (Ala-too in Kyrgyz), you will indeed spot yurts dotting the slopes with flocks of sheep nearby in an idyllic picture of nomadic life.

But, it can be a little disappointing for felt enthusiasts to arrive in modern Bishkek and hardly find a yurt, or even a felt, in sight.

In Kyrgyzstan’s capital city -- population about one million -- yurts today are only set up in the garden of someone’s home when a family member dies. The lady of the house faces the inner wall of the tent each time mourners approach the house and start a dirge. Female newcomers join her in lamenting, while men remain standing outside, facing the wall of the yurt and wailing.

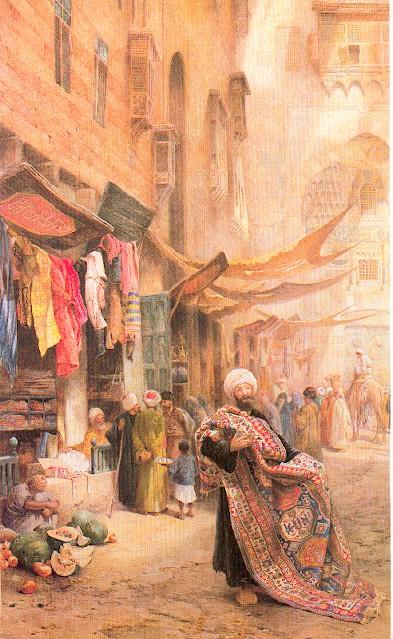

Even in the marketplaces it is hard to find nomadic felt carpets. The carpets for sale are machine-woven imitations of sophisticated Turkmen and Iranian pile carpets.

Janyl Chytyrbaeva, a Kyrgyz journalist, explains why. “Everyone wants a house like you see on TV,” she says. The machine-made carpets from artificial fiber are given as gifts at weddings and funerals and most people’s apartments and houses are covered with them.

Does this mean that felt has disappeared from Kyrgyz life? No. But like so many traditional handicrafts elsewhere, it is endangered and its only protectors are female artisans from poor rural area and artists.

Chytyrbaeva, who herself stitched her own felt dowry rugs as a teenager, says the only place to find it in use in Bishkek is where the poorest migrants from the countryside have settled on the outskirts of the city. There, they cover the floors with plain yet colorful felt mats or with patterned Ala-Kiyiz, which are made by rolling colored felt into a plain felt background. More highly patterned carpets, Shyrdaks (Shirdaks, Shurdoks), are made by sewing together felt of different colors and then stitching them onto a plain felt basecloth.

All these kinds of felt carpets provide warm flooring in a country where the winters are bitterly cold. For additional warmth, laborers’ families will also put sheepskins here and there on top of the felt. Sometimes, pieces of sheepskins with black, brown, or white wool are stitched together to give these mats, too, an interesting shyrdak-like pattern.

Still, if these furnishings seem humble, the ancient felt-working tradition of Kyrgyzstan itself is rich. Skilled felt-makers can produce pieces of effortless sophistication and great art just as readily as ordinary villagers make plain felt floor mats.

Still, if these furnishings seem humble, the ancient felt-working tradition of Kyrgyzstan itself is rich. Skilled felt-makers can produce pieces of effortless sophistication and great art just as readily as ordinary villagers make plain felt floor mats. Highly complicated Shyrdaks are created by cutting the same design into several sheets of brightly colored felt and then switching and refitting the pieces together like jig-saw puzzles.

The flowing and harmonious patterns, filled with symbolism, complement the unstructured texture of the felt. With additional techniques, including appliqué, more detailed designs become possible.

The flowing and harmonious patterns, filled with symbolism, complement the unstructured texture of the felt. With additional techniques, including appliqué, more detailed designs become possible.Kyrgyz felts are gradually gaining a place in the Western market, yet they still remain little known compared to the other great textiles of Central Asia: the red pile rugs of Turkmenistan or the Suzani embroideries of Uzbekistan.

A handful of rug importers are scouring the Kyrgyz countryside for artisans but many more Western businesses seem content with just importing Kyrgyz-made felt slippers and hats or, more recently, stuffed toy animals.

That seems modest for a nomadic culture that in many ways was unique. The Kyrgyz, who live in a mountainous country, migrated up and down their slopes with the seasons while most of their steppe neighbors wandered widely across the plains.

That seems modest for a nomadic culture that in many ways was unique. The Kyrgyz, who live in a mountainous country, migrated up and down their slopes with the seasons while most of their steppe neighbors wandered widely across the plains.Today, they can date their presence in the mountains to thousands of years ago and have many traditions all their own. That includes the design of the national flag. It is the only one in the world that has at its center a stylized representation of the roof of a traditional yurt.

#

RETURN TO HOME PAGE

#

Related Links

Kyrgyzstyle Company, Kyrgyzstan

FeltRugs Company, Britain

Shirdak Silkroad Textile Company, Netherlands

Photos of Kyrgyzstan: Jonathan Barth

YouTube: How Nomads Make Felt (Mongolia)